Explore on Amazon

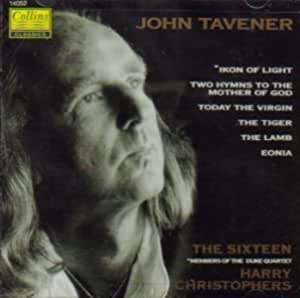

JOHN TAVENER – ‘IKONS OF LIGHT’ FESTIVAL

JOHN TAVENER

Tavener once said to me. “As time goes on the music that I write teaches me.” For a composer whose wellspring of creativity is his belief in the divine this is an important revelation. He went on to say that “art is not limited if one allows the Holy Spirit to enter, and the only way to allow it to enter is by way of dissolution, and by that I mean total dissolution in the literal sense, at the point of nothingness, when one is absolutely nothing – can do absolutely nothing, only then can the Holy Spirit come in and work within you.”

Shortly afterwards I had the privilege to be amongst the first to see the score of Ikon of Light. As I remember, Tavener was very nervous about the reaction this work might have both on the musical world and his audience, but as I read this extraordinary score it was clear that Tavener had successfully found a way to marry his faith with his musical creativity. It is particularly fitting then that the Ikon of Light should be included in the forthcoming Tavener Festival Ikons of Light at the South Bank, for it was perhaps this work more than any other that paved the way for much of the music that Tavener has written since.

Of course, a great deal has developed in Tavener’s thinking since; his interest in Eastern philosophy and spirituality has widened to embrace not only his Orthodox faith, but also other Eastern cultures including Indian and Iranian Sufi music, as well as some more unexpected and surprising sources of inspiration. If we consider the primary characteristics of Persian music – its use of microtones and gushehs (modal scales), its predominantly monophonic nature, its use of substantial pauses within the musical structure and the emphasis on symmetry and motivic repetition at different pitches – we can immediately understand Tavener’s empathy with a tradition that shares so many characteristics that were already integral aspects of his own musical ethos. These characteristics can be clearly heard in Tavener’s recent Fall and Resurrection, premiered to much acclaim early this year, where he also employs Eastern musical instruments such as the Kaval, Tibetan temple bowls and a Ram’s Horn trumpet.

When I caught up with John to talk about the festival he had just returned from a strenuous visit to American where, among other engagements, he had conducted a performance of A New Beginning in New York, which was originally commissioned for the opening of the Millennium/Greenwich Dome and which can be heard again in this festival, only this time without the hubbub and celebratory paraphernalia of the first performance. We talked about some of the performances that are to take place during the festival, including Nipson (Cleanse) for counter-tenor and viol consort, which is based on a Byzantine palindrome inscribed on a fountain in Constantinople. “It’s set in Greek” says Tavener” and the words of the palindrome are ‘cleanse the sins not only the face’. I’m looking forward to it very much, Michael Chance sings wonderfully.” he says.

Tavener was also keen to talk about The Fool for male voice and strings, which will receive its London premiere at the festival by the Gogmagos, an extraordinary group of string players who also introduce choreographic elements into their performance. The work is based on the theme of the Holy Fool with a Beckett-like libretto by Mother Thekla. “Byzantine Fools” Tavener explains, “used to do outrageous things: they would attempt to rape married women or get drunk and eat vast amounts of food on Good Friday, and their reason for doing it was to rout out the hypocrisy either in the marriage or in the Church. It’s quite a difficult concept for any western audience to grasp. For instance the fool in Shakespeare is quite a different thing. The Holy Fool on the other hand has reached such state of apatheia [dispassion or literally ‘purity of heart’] that he has completely removed himself from his acts and so he therefore gains no pleasure out of it.” Tavener’s musical response to the subject matter reflects the topsy-turvy world of the Holy Fool “Everything he sings at the beginning is very outrageous and is compositionally absurd, but by the time he gets to the end he hardly exists at all. In the scene set at Christmas – he is surrounded by people getting drunk and he is a sallow shrunken looking figure who just looks at an empty glass – whereas in the scene set at Easter he lies in a heap on the floor while people are getting drunk around him. He sings the line ‘he has given life’ but nobody listens and it ends up with the Gogmagos laughing and taking no notice of him, whereas when he was doing outrageous thinks they took great notice of him” I was intrigued to discover that The Fool is dedicated to Norman Wisdom: “He moved me so much when I was young. I found him funny and he made me cry” Tavener explained “and when I saw him recently in Chernobyl where they named a hospital after him and what he did for those children who are dying of cancer I decided to dedicate The Fool to him.”

Also featured in the festival are works by composers for whom Tavener has a particular admiration, among them Handel, Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky, as well as an all night concert featuring Sufi music, and a concert by the Byzantine Choir of Lykourgos Angelopoulos. Tavener confessed that he had not really listened to much Handel until a few years ago when he discovered a wonderful recording of Solomon, and since then has developed a passion for his vocal music. “I think it’s Handel’s spontaneity more than anything that I like, and also the fact that he never does what you expect him to. Unlike Bach, when he starts a fugue he doesn’t go through all the motions, he’ll go off at a tangent and stop the fugue and do something amazing. I’m also knocked out by his amazingly beautiful vocal lines, especially the vocal lines he wrote for women. The music he wrote for the Queen of Sheba, or Solomon’s wife is some of the most exquisite female music every written.”

Tavener has often remarked on the lack of the ‘sacred’ in twentieth century music, and the prevailing fascination with complexity is certainly at odds to his way of thinking. Tavener explains, however, that he often discovers unexpected areas of interest via his own Eastern influences. “The less interested I become in music from the German western tradition, the more it leads me not only to Indian music and Sufi music but also to musicians like the American saxophonist John Coltrane whom the American Black Orthodox church have made a Saint. Again, like Sufi music, jazz is a music that cannot really be written down, and Coltrane’s playing has a wonderful ecstatic quality in the same way that chant has. Webern is ecstatic too. I have grown to love Webern more over the years. The last cantatas are wonderful. I really think that since Hildegard von Bingen you have to wait a long time before you get anything like it, but it happens in Webern. Nobody talks about the religious ecstasy in Webern – there’s so much beyond the mere notes – he transubstantiates whereas his imitators do nothing. If I had to name one composer who stood out in the twentieth century it would have to be Webern.”

Interview © Michael Stewart & John Tavener 2000

All content © Michael J. Stewart

Buy on Amazon